Guardsmen returned triumphant from Europe after World War I, but few ever served again.

1919 could have presented many challenges for the Guard given the potential for call-ups prompted by the Red Scare that produced lots of domestic tension and turmoil during the year after World War I.

A police strike in Boston and larger strikes targeting Seattle and the steel and coal industries could have pressed the Guard back into the strikebreaking duties it had performed in the decades before. There was also racial strife in several cities, including Chicago and Washington, D.C.

But municipal police forces, the Army, and State Guard forces dealt with the troubles in 1919. The National Guard? It had all but ceased to exist.

It took several years for some determined Guard officers and members of Congress to put that house back in order. The actions of the interwar years comprise one of the lesser known but hugely significant chapters of the Guard’s history—a period when the battleground was Capitol Hill and the halls of the War Department, not some faraway land.

“There was no National Guard from 1919 to 1920,” says Len Kondratiuk, the National Guard Bureau’s former chief of Historical Services. “The only existing military forces in the states were those [approximately 30] states that had State Guards. They were limited. They were smaller organizations, not well equipped, not well trained.”

Guard strength was woefully weak nine months after the Armistice ended the fighting 100 years ago this month. Only 36,013 troops were “with the colors” even though the War Department had authorized 120,109 citizen-soldiers nationwide, reported The New York Times in August 1919. Although Texas and Minnesota exceeded 100 percent strength in July 1919, the newspaper reported, “Twenty-seven States and Porto (sic) Rico show no enrollment.”

The Guard had all but evaporated when the Army discharged conscripted soldiers as they came home. This included 400,000 Guardsmen who were drafted as individuals into federal service in August 1917 so they could be shipped overseas. Such was the law at the time governing the use of the Guard overseas.

“That released them from any obligation to National Guard service,” Kondratiuk explains. So when the Guard divisions came home, soldiers weren’t returned to their states because they weren’t actually members of the Guard, even if they had been before they were drafted. “If you had a three-year enlistment, you no longer had to serve that,” Kondratiuk adds.

That was just fine with the vast majority of soldiers, especially the veterans of the Western Front who had experienced the horrors of the world’s first industrialized war. They had also suffered from or witnessed the ravages of the worldwide Spanish flu pandemic that accounted for about half of all military deaths.

The numbers were staggering on both counts.

Some 103,731 members of the Guard’s 18 divisions, nearly a quarter of their 440,000 troops, were killed or wounded, according to Guard records. The flu, and related pneumonia, killed about 45,000 U.S. soldiers in 1918 in addition to the 53,402 Americans killed during eight months of intense combat, according to a New York Guard report. Doctors with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) hospitalized 340,000 soldiers for influenza during 1918 while 227,000 soldiers were in the hospital because of battle wounds and the effects of poison gas.

Furthermore, Guard casualties were frequently replaced by other draftees, men who never had any allegiance to the Guard. That included many of the 17,253 replacements sent to the Guard’s 42nd “Rainbow” Division and the 14,411 who replaced the dead and wounded in New England’s 26th “Yankee” Division, according to Kondratiuk’s numbers.

So who could blame those guys for not jumping at the chance to join the Guard after the war? Who could blame a combat-seasoned former doughboy in Maine, when asked by someone in uniform why he didn’t join the Guard, for answering: Sonny, why don’t you go ta hell?

Certainly not Army Col. Fitzhugh Lee Minnigerode who concurred with AEF commander Gen. John J. Pershing’s assessment that the Guard had distinguished itself on the battlefields of northern and western France.

“It ought to be a splendid and invaluable institution,” Minnigerode wrote in The New York Times in November 1920. “But it is almost a waste of time to attempt to recruit from among the returned service men. They have been to war. They have reached the goal all men entering military service long to attain and they are through for the time being, at least.

“Young men, those now coming of military age, are the material from which to reconstruct the machine. ... The task now confronting all men anxious to see the guard [sic] resurgent is to talk for it, think for it, work for it.”

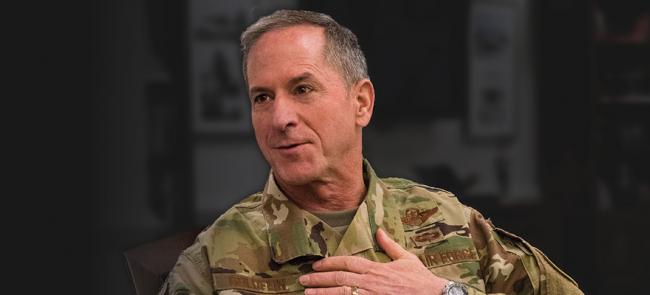

There was no National Guard from 1919 to 1920.

Len Kondratiuk

Former chief of Historical Services, National Guard Bureau

GUARD LEADERS ended up following Minnigerode’s course of action. The result was a post-war National Guard that is remarkably similar to what we have today and considerably different from what had existed before.

“Everything that we think of today really starts in the 1920s. It was a dedicated, hardcore group of career National Guard officers who stepped forward,” says Kondratiuk. “The cadre that restarted the units after the war were all pre-war Guardsmen and were in the Guard divisions during the war.”

The initial prominent proponents in 1919 and 1920 included Maj. Gen. John O’Ryan of New York and Maj. Gen. Milton Reckord of Maryland. Two major generals from Minnesota, Ellard Walsh and George Leach, stepped up later in the ’20s and into the 1930s, to help ensure that the Army could not disregard the Guard.

They were men of substance. All four commanded troops in France. O’Ryan was the Army’s youngest World War I division commander and the only Guard general who led his outfit, the 27th Division, for the duration.

O’Ryan, Reckord and Walsh became their states’ adjutants general. Each served terms as NGAUS president. Leach spent four years as chief of the National Guard Bureau. O’Ryan was one of the American Legion’s founders. Two had studied law.

They lobbied long and hard to secure a prominent role for the Guard in the national defense strategy. They proved to be as capable and influential as communicators after the war as they had been as commanders during the final year of fighting.

They subscribed to the philosophy of one John McAuley Palmer, an 1892 West Point graduate and Regular Army officer. He was influenced by his Civil War general grandfather who believed that military leadership should be open to “able civilians,” not just professional officers. Palmer served on the Army General Staff. In France, he was the AEF’s assistant chief of staff for operations and then commanded a brigade in the Guard’s 29th Division during the final three climactic months.

Palmer believed the country would best be served by a small Regular Army and a reliable, organized citizen reserve of the Guard and Army Reservists who could get additional training if they were mobilized. “The patriotic young men of the National Guard are the real founders of the American army of trained citizenry. All honor to them that they maintained the tradition of that great national ideal,” stated Palmer in his 1916 work An Army of the People.

“The time has arrived when verbal patriotism should be translated into organized security by swelling the ranks and attaining the highest efficiency in the organizations of the National Guard in this State,” stated O’Ryan in his appeal for all former officers and soldiers to join the reorganized 27th Division, reported The New York Times on Dec. 21, 1919.

It had been necessary to wait a year, O’Ryan claimed, “to give officers and men a period of rest uninterrupted by military duty of any character and to learn, if possible, something of the attitude of Congress in relation to reorganization.”

Many people, including governors, were anxious to learn the same thing. On one hand, “most Governors were willing to await the outcome of defense debates in Washington before expending scarce resources on the Guard,” wrote Guard historian Michael Doubler. On the other hand: “Several States clearly understood the importance of having a peacetime force for domestic disturbances and natural disasters,” he added.

The National Defense Act (NDA) of 1920 resolved the issue. Congress rejected Army leadership’s call for a half-million-man full-time force backed up by a vast reservoir of federal reservists who would undergo universal military training. That proposal didn’t include the Guard. Service leaders pushed the same course after World War II.

But Congress understood that Americans remained suspicious of a large standing army and were satisfied that the Navy was the first line of defense for America, which was protected from foreign foes by two oceans. Such a force was also costly. A smaller active force reinforced by standing units of the Guard and individuals of the Organized Reserves is what they got, Doubler explained.

It is almost a waste of time to attempt to recruit from among the returned service men.

Col. Fitzhugh Lee Minnigerode

Writing in The New York Times, November 1920

THE 1920 LAW created the “Army of the United States” that authorized 298,000 regulars and a maximum of 435,000 Guardsmen, principally in 18 divisions. It designated the Guard as the nation’s primary combat reserve and, in effect, the largest military force in the land, although congressional appropriations limited the growth to about 180,000 through the 1920s.

“We have gone a long way since the almost fatal days of 1917 and 1918,” Reckord wrote in the July 1932 Baltimore magazine. “The whole status, organization, equipment and training of the National Guard have been changed. The entire military system of the United States has been made an effective nucleus for a genuine citizen army, for a well-regulated militia closely following the line proposed by General Washington.”

Kondratiuk insists that the 1920 act merely modified the 1916 NDA, which he considers the foundation of the modern National Guard. It’s just that the 1916 law “was never acted upon because we had the Mexican border call-up and World War I. So it’s really 1920 that the act of 1916 kicks in for the Guard.”

The upshot was that Gen. George Washington couldn’t have imagined the ways in which the militia evolved into a 20th-century force. The massive reorganization took about six years, until 1926, Kondratiuk says.

The War Department started authorizing and federally recognizing Guard units, and recruiting skyrocketed. “In less than two years, manpower nearly tripled to an all-time [peacetime] high of 159,658 soldiers,” wrote Doubler. “By the summer of 1922, all states except Nevada had organized Guard units, and 20 states had completed the reorganization of all units authorized.”

New York was a case in point. Of the 17,805 men in the Empire State’s military forces at the end of 1919, only 2,386 “were members of the National Guard recognized by the War Department,” stated O’Ryan in his adjutant general’s report to the governor. A year later, 10,474 of New York’s 17,670 soldiers had received federal recognition.

“Most of the recruits had no military service, but the cadre was prewar and wartime Guardsmen,” Kondratiuk explains.

The Guard changed in other ways. Most of the venerable, elite militia units, which were as much social clubs as military formations, faded away. New types of units, with new equipment, including airplanes, began being incorporated into what had essentially been an infantry force, with some artillery and horse cavalry, that was mobilized for World War I.

The new assets included medical, quartermaster and signal units, and maintenance units when trucks started rolling in. Armor companies, with tanks, and aerial observation squadrons became elements of the Guard’s 18 reorganized divisions whose new tables of organization and equipment (TO&Es), mirrored those in the Regular Army.

It took time for all of this to transpire. In general, northern states had the large armories that could accommodate the new equipment essential for the new missions; whereas southern states needed time to construct armories and other facilities for new units.

The 34th Division in Minnesota benefited early. It received the Guard’s first tank company, in Duluth, in May 1920. The 109th Observation Squadron was the first flying unit to receive federal recognition in January 1921.

Mississippi’s 114th Field Artillery Regiment, on the other hand, was not reorganized until 1925 due to a lack of funds required to build stables and corrals for the horses that towed the guns. The chief of the Militia Bureau’s reports of 1923 and 1924 indicated that a shortage of funds slowed the Guard’s reorganization, Kondratiuk says.

Still, Guard soldiers began annual training exercises as early as1920, and trucks started transporting troops to maneuver centers for the realistic training that leaders seasoned by war knew their soldiers needed.

The interwar decades when the Guard was reconstituted are a study in contrasts. “Perhaps there has been no period in American history quite like the contrast between those two decades between wars ... the boisterous, gilded Twenties and the dark, depression-haunted Thirties,” wrote Virginia Brainard Kunz in Muskets to Missiles, her 1958 history of the Minnesota Guard.

The pay Guardsmen received was a common denominator during those dichotomous decades, according to historians. The dollar per drill, as well as money for two-week camps, was a recruiting incentive in the ’20s. But the $75 a year a private earned triggered a surge of volunteers in the ’30s. Many units had waiting lists for the first time, and Guard strength soared to a peacetime high of 187,413 soldiers in 1932 during the depth of the Great Depression.

But some people enlisted out of pure patriotism. A certain New York Yankee slugger joined New York’s 104th Field Artillery Regiment to much fanfare in 1924. A dollar a drill likely was little inducement.

The 1920 TO&Es for the reorganized divisions got the Guard back into the air and "finally placed aviation on a permanent footing in the National Guard."

Charles Gross

Air National Guard historian

THE ’20S ALSO BROUGHT the phenomenon of flight to the Guard’s 18 divisions that led to the creation of the Air National Guard as part of the Air Force in 1947.

“The Air Guard exists because the 1920 division TO&Es included an observation squadron in every Guard division,” Kondratiuk says.

That was an important first step, agreed former Air Guard historian Charles Gross. Lobbying was the second critical step, and the TO&Es gave aviation advocates the leverage they needed, he added.

“Initially, military officials did not want to put resources into actually forming those squadrons,” Gross wrote. “Then a number of people who were Army aviators in World War I started lobbying the Guard and the Army to form those units. They talked to governors. They went to Washington. If those aviators hadn’t actually lobbied to fill out those units that were authorized, the Air Guard, or National Guard aviation as it was called in those days, probably would not have gotten started at that point.”

“They found an enthusiastic ally in Army Air Service General Billy Mitchell who believed that the National Guard would help promote the general development of commercial and military aviation in the United States,” Gross said.

The availability of large stocks of surplus wartime equipment, apparently including airplanes, helped the cause.

The Guard had been flirting with flying for years before Minnesota’s 109th Observation Squadron got its federal recognition in 1921, according to Gross’ timeline.

Ballooning sparked the interest of some New York City Guardsmen in 1908, and aeronautical detachments were formed in Missouri and California in 1909 and 1911. Nebraska began experimenting with military aviation in 1913. Corporations donated thousands of dollars so that the private Aero Club of America could fund pilot training for Guardsmen in Arizona, California, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island and Texas.

New York’s 1st Aero Company became the Guard’s first genuine aviation unit in November 1915. Its wings were clipped when it was mustered out of federal service a year later, and it was disbanded in May 1917.

By then, the War Department had ruled out mobilizing any Guard air units for wartime flying. All of the units were disbanded, and aviators anxious to fly over there had to join the Signal Corps Reserve. About 100 Guard pilots wound up in the newly formed Army Air Service. Four became aces, and one received the Medal of Honor posthumously.

The 1920 TO&Es for the reorganized divisions got the Guard back into the air and “finally placed aviation on a permanent footing in the National Guard,” Gross wrote.

The 135th Observation Squadron in Alabama got its federal wings in January 1922, a year after Minnesota’s 109th. New York’s 102nd squadron, with 15 Army JN-4 “Jennies,” received its recognition that November. Guard squadrons gradually began getting newer, faster observation planes thanks to the 1926 Air Corps Act.

Seventeen more squadrons joined the flying fraternity within the next 16 years, and the Guard’s interwar tally vaulted to 29 squadrons when 10 were organized from 1939 to 1941, “reflecting growing international tensions and preliminary efforts to prepare for a possible conflict,” Gross explained. Aircraft authorized for each squadron increased from nine to 14 in 1939.

While the 1920 NDA reconstituted the Guard, it didn’t provide a mechanism for Guardsmen to return to a state status the next time the president called them. NGAUS and Guard supporters developed a novel solution that Congress passed in 1932 as an amendment to the 1916 NDA.

It established the “National Guard of the United States” as a permanent reserve component of the Army consisting of federally recognized, deployable Guard units. At the same time, it identified the “National Guard of the several States” consisting of voluntary members of the state militias that served under the governors.

Henceforth, Guardsmen would be members of both organizations, which enables them to move back and forth between state and federal statuses, institutionalizing the Guard’s dual role, Doubler wrote. The legislation also changed the Militia Bureau to the National Guard Bureau.

BOB HASKELL is a retired Maine Army National Guard master sergeant and a freelance journalist in Falmouth, Massachusetts. He can be contacted at magazine@ngaus.org.

Flu a Bigger Killer Than War in 1918

IN THE AUTUMN OF 1918, there were two big killers in the world.

World War I, which would claim 20 million lives by its end, and a flu pandemic, which killed at least 50 million people worldwide.

The Spanish flu struck an estimated 500 million people, nearly a third of world’s population. The average lifespan worldwide dropped by 12 years.

American combat deaths in World War I totaled 53,402. But about 45,000 American soldiers died of influenza and related pneumonia by the end of 1918.

More than 675,000 people in the United States died of influenza that year. Based on today’s population, that would be the equivalent of 2.16 million Americans.

Many medical historians believe the virus originated in Haskell County, Kansas, and the U.S. Army helped move it along.

In January and February 1918, according to the 2005 book The Great Influenza, Dr. Loring Miner, a local physician, discovered people in the sparsely populated county were coming down with a particularly virulent flu strain.

In the past, it might have never gotten beyond Haskell County, but in 1918, the Americans were traveling around the world.

Young men from Haskell County trained at nearby Camp Funston, what is now Fort Riley, Kansas. They brought the virus to the camp. And because troops moved among the Army’s camps all across the country, it went national.

On March 18, Camps Forrest and Greenleaf in Georgia reported influenza cases. By the end of April, 24 of the Army’s 36 main camps noted outbreaks. That same month, influenza hit Brest, France, one of the major debarkation ports for American soldiers.

The disease jumped enemy lines. German General Erich Ludendorff, who led Germany’s spring 1918 offensive, remembered in his post-war book that he despaired because so many troops were sick and not on the frontlines.

The death rate, however, wasn’t unusually high. The virus disappeared that summer. But in the fall it had mutated and came roaring back. Now it was a killer. And most flu deaths were of healthy young adults, who died from bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by the influenza.

In Europe, American Expeditionary Force (AEF) doctors hospitalized more troops (340,000) for influenza in 1918 than for battle wounds (227,000).

In October 1918, as the American Army battled the Germans in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the flu began taking toll on combat effectiveness. Ludendorf noted Oct. 17 that the fighting power of the allied forces “has not been up to its previous level ... the Americans are suffering severely from influenza.”

Meanwhile, sickness and death at training camps back home prompted the Army to stop training new troops. Army Surgeon General Charles Richard also recommended against shipping more soldiers to France until the flu pandemic stopped, but President Woodrow Wilson decided against it.

The AEF was on the attack. The Germans were retreating. The war’s end seemed near.

Fortunately, the pandemic ended not long after Germany surrendered, as resistance to the virus increased.

—By Eric Durr