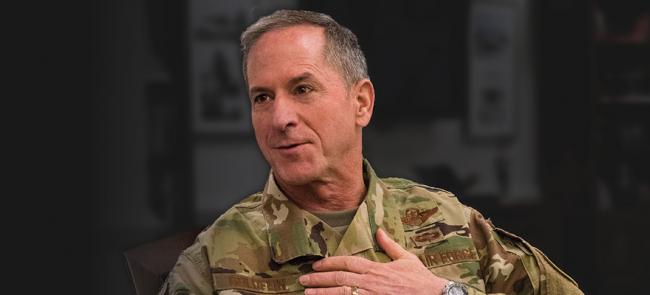

As chief of the National Guard Bureau, Gen. Joseph L. Lengyel answers directly to Defense Secretary James N. Mattis.

But it’s not the first time the Texas Air National Guard officer has worked for the former Marine general. Lengyel was chief of the Office of Military Cooperation and defense attaché in Cairo, Egypt, in 2011 and 2012 when Mattis was the commander of U.S. Central Command.

And Lengyel remembers to this day some advice he received from Mattis.

The two were riding to the Ministry of Defense in Egypt one day in 2012. Lengyel had just learned that he would soon receive his third star and become NGB vice chief. He mentioned that the active component and the reserve component sometimes looked through different lenses, which often led to tension when resources became tight.

“The only lens that ever matters,” Lengyel says Mattis told him, “is the lens of the national defense and national security of the United States.”

Both appear to be looking intently through that lens these days. Mattis released a National Defense Strategy earlier this year that shifts the focus of the U.S. military from combating global terrorism to major-power competition. And Lengyel is working to shape the National Guard to fit the new paradigm.

Lengyel sat down recently with NATIONAL GUARD to talk about the National Defense Strategy and other matters important to the National Guard and members of the force.

The new National Defense Strategy aims to better orient the U.S. military to the rapid changes in the global security environment and the fundamental shifts in the character of war. Your testimony and speeches indicate the National Guard will play a significant role in this new strategy. Readiness demands have already increased for some units. How else must the Guard adapt to fulfill its role in the new defense strategy?

The dedication of the department to implement the National Defense Strategy has affected every component. This operational force that we have become as part of the United States Army and the United States Air Force is illustrative inside the National Defense Strategy on how we will play inside the future global operating model. As this strategy retunes itself for global peer competition, it’s crucial that we make our force more ready and more lethal.

As time goes on, all the attributes that we bring to not only the warfighter piece of this thing, but in the allies and partners piece, is critical. So we’re just going to keep doing what we’ve been doing really since the first Gulf War when we began this journey as this operational force and stay on path.

But the Guard will have to be faster to the fight?

The Guard will have to be faster to the fight, faster than we used to be. Still, I think, the best use of our force is to posture against known requirements. We still have a business model where the men and women of the National Guard have civilian lives and jobs. We need to, to the degree we can, maintain our commitment to that business model.

The Air model has always been a fast-response force at near what the active component is. The Army model has changed significantly to reduce our post-mobilization times. But we still need predictable dwells. We need to be predictable so our soldiers can resume their lives as civilians and then plan and train for known deployments as circumstances allow. Barring a huge war where everybody is in, we need to maintain that connection to our business model.

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis’ signature is at the bottom of the National Defense Strategy’s executive summary. You work for him. What has he shared with you about his impressions of the National Guard?

You know, broadly speaking, Secretary Mattis sees and values the contributions of the reserve component, particularly the National Guard, for what we bring to the warfighter piece of our mission.

I’ll share a story. I worked for General Mattis when I was in Egypt as a defense attaché in Cairo [Egypt in 2012] when I was selected to be vice chief of the National Guard Bureau. I recall one time when we were driving to a meeting at the Ministry of Defense in Egypt, he gave me some pointers on my promotion to lieutenant general and this new role. I mentioned how the active component and the reserve component sometimes looked through different lenses and how that can cause tension between the two components, especially when money is tight and there is competition for resources. And he said: It doesn’t matter what component you are in or what your job is. The only lens that ever matters is the lens of the national defense and national security of the United States.

That was pretty good advice. If you make your plan based on what’s best for the defense of the United States, then you’ve got a pretty good chance at the end of the day to have a winning argument.

Greater demands on the force mean greater demands on families and employers. Is it time for the nation to discuss providing a little more support to those who enable traditional part-time Guardsmen and Reservists to serve?

We’ve come a long way since the first Gulf War and the last 18 years in the Middle East with duty-status reform and finding benefits and easier ways to access Guardsmen and Reservists and to make sure their families were better taken care of. But there is more work to do.

Part of that is the ongoing duty-status reform piece that should normalize pay, benefits and other entitlements for the Guardsmen and Reservists. I acknowledge that it’s going to be a couple of years before we can get all the required legislation. I think organizations like NGAUS are critical to stay on that, to keep us focused on making sure that soldier, that airman and their families are well taken of, that there is parity of benefits. And it’s very important that we continue to work to do that. We’re such a big part of the national defense of the United States now. We, as a nation, need to make sure that families are cared for appropriately.

How about employers?

Absolutely. We have to do the best we can to maintain predictability for our employers. When we mobilize large formations in towns and cities, we sometimes remove large portions of police departments, large portions of fire departments. Predictability is key. And to the degree that we can, we should offer employers financial incentives to hire Guardsmen. There is always that trade-off of the cost of the reserve component and our value.

And so, there have been plenty of proposals out there that offer tax incentives to employers and those kind of things. I fully support our ability to give employers incentives to hire not just veterans, but currently serving members of the National Guard and Reserve. I believe that’s important.

The new strategy calls for a more lethal, agile force that better leverages emerging technology. How could such a Guard force also be more effective in domestic response?

Everything we do, broadly speaking, inside the domestic realm flows from our wartime skillsets. So as technology rises in importance in general society, it will also rise in importance in the military. Cyber is a good example of this. How do we protect power grids and critical infrastructure? We can use National Guard skillsets here. You’re seeing the growth in the space mission and I believe the National Guard will continue to have a presence in the Air Force space mission. As we become a more operational and lethal force, our homeland response capabilities will also improve—meaning the nation and communities we serve will all benefit.

The National Guard State Partnership Program just celebrated its 25-year anniversary. What started in three Baltic nations now links National Guard states and territories and the District of Columbia with 81 separate nations around the world. We often hear senior leaders sing the praises of SPP. What do your colleagues in the Pentagon say to you about the program?

It’s in the combatant commands where people really sing the praises of the State Partnership Program. In their areas of responsibility, they deal directly everyday with our partner nations. They see the direct impact and value that our partnerships have. They’ve seen us build relationships and strengthen alliances. They’ve seen us build capacity, actually deploy and fight alongside some of our partner nations. I think the other service chiefs, particularly the Army and the Air Force, also see it. They recognize it. They understand the value of it. But, really, with the boots-on-the-ground piece of it, this impacts the combatant commanders the most.

I also hear it from the State Department, from the ambassadors and our diplomats. They see it and express great appreciation for the role the National Guard has in bringing some of the values we have in our military, like civilian control, the rule of law, human rights. As we bring those to other nations and share those with our partners, it’s hugely lauded by the State Department.

The Army’s Big Six modernization priorities are in line with the National Defense Strategy. The new systems should bring greater lethality and agility, while addressing the eroding competitive advantage the United States has over Russia and China. Will the Army National Guard be a full partner in this effort?

The Army Big Six is fundamental to the execution of the National Defense Strategy. We’re going to make a ready force and we’re going to modernize the force for the future warfight against peer competitors. So, as the Army modernizes the force, the National Guard will be part of it. Same thing with the Air Force, as the National Commission on the Future on the Air Force recommended.

We used to modernize the active component first and then cascade all the old equipment into the Guard and Reserves. That model doesn’t work. The days of having old force structure in the reserve component, different force structure from the active component, is no longer a relevant model. Concurrent and balanced recapitalization of the reserve component while they recapitalize the active component is really kind of new.

And we have teams embedded on the Army Big Six programs, whether it’s Future Vertical Lift and all the things that are coming about the Next Generation Combat Vehicle. All of those things are relevant to the future of the Army National Guard and Air National Guard.

The Army National Guard has several modernization programs addressing legacy systems that are years from being complete. Will the Army’s Big Six priorities push some of them to the right?

There is always competition for resources. I don’t want to talk about the future specifics of the budget, per se, that are out there. The Army will make the decisions that give them the most lethal force they can have, the most ready force they can have. And they’ll make investment decisions along those lines. And whether it pushes some programs to the right or cancels some programs, I am not really at liberty to say. But I think that whatever the Army does going forward to modernize, recapitalize the force, the Army National Guard will be a part of it.

The National Defense Strategy links “sustained and predictable investment” to making the military “fit for our time.” The fiscal 2018 defense budget includes a significant boost in defense spending. So does the fiscal 2019 budget; however, we may open the fiscal year on a continuing resolution. And spending caps return in fiscal 2020. How concerned are you about a return to fiscal challenges?

I’m very concerned about it. I think all of the chiefs have stressed one of the most important things we need in our force is a predictable line of funding. So, for us, when we have continuing resolutions, we don’t have known levels of funding and we have to use last year’s budget until we get the new one approved. Much of our budget for, in particular, state partnerships and congressional additions, we don’t get that money until we have an appropriation.

So I think that stable funding is crucial to our readiness of our force. Nothing degrades the readiness of the force more than unpredictable funding.

The Guard seems to be especially susceptible to the problems of continuing resolutions and government shutdowns. Earlier this year, a drill weekend was cancelled due to a shutdown. That caused quite a bit of disruption. Do you think Congress and the American public understand the impact here?

Well, I certainly make sure they understand that. Every time I testify, I explain that it’s disruptive to us and for our readiness to have to cancel a drill. I’ll give you an example. The Army National Guard conducts most of its collective training in the summer months. As a result, we schedule contract medical examinations for the fall and winter months. When we cancel a drill, we have to cancel that contract support because the soldiers aren’t coming in to get it done. You have to reschedule that later, often at a time when we want to be out training. We also use a lot of contract support for meals and transportation. That kind of support can’t just be turned off. If we have to cancel a drill at the last minute, that food and those buses go to waste. Yet, the contracts have already been let and we have to pay for them.

And it just treats people wrong. For us, these soldiers and airmen are talented people and they have other choices. They serve in our National Guard because they want to, not because they have to. You make it disruptive when they travel long distances and you have to tell them to go home. Finding, recruiting, training and retaining our force is some of the most important stuff we do. Every time we cause disruptions, we risk somebody saying, I don’t have time for this anymore.

Recruiting and retention have become more difficult lately, especially in the three components that make up the Army. Some say the current generation has a lower propensity to serve. Others cite the strong jobs market. Still others say increasing demands on the force are to blame. What do you think? And how do we overcome current recruiting and retention challenges?

I think it’s a combination of a lot of things. Much of the current challenge in the Army is trying to grow after years of cutting end-strength. It’s hard to turn that around at the bottom. We’ve been trying to decrease and now we’re trying to ramp back up. Part of it is that and whether we had all the indications and warnings that we needed to turn it around sooner. Maybe we’ve learned something there.

I think there is also a competitive job market. Unemployment is low, the economy is strong and some people don’t have time for the Guard and Reserve. That is a piece it. Are we training too much? Have we gone [overseas] too much? I lived this on the Air Guard side back in the early ’90s when we had this continuous rotational deployment for Operation Southern Watch and Northern Watch and we got into the groove. Some people found it was more than they had signed up for as citizen-airmen. Some people adapted. Some people changed into less-demanding roles inside the National Guard. I think we should consider our messaging a bit. Thirty-nine days a year is not the standard model now for most of the National Guard. Our operational force requires more than 39 days a year in some cases.

The soldiers and airmen I’ve talked with want to be deployed. If they’re going to invest a lot of time training, we need to find a meaningful deployment where they can use that training. That way, employers and families can see why we train so hard. Not deploying can actually be a negative impact on recruiting and retention. So that’s a challenge. We’ve got to stay focused on the message. We have to stay focused on competing with the other components, applying bonuses and retention incentives to get people to stay. It’s just become a very complex challenge to recruit and retain the force.

There is a lot of concern in the ranks about the length of the federal-recognition process for officers in the National Guard. Defense Department data from earlier this year indicated that more than 6,500 Guard officers were waiting an average of 265 days in the fedrec queue. What can be done in the Pentagon to accelerate the process?

This has been a problem, particularly for the last year. I know [Army] Secretary [Mark] Esper has been directly involved with this. I think the requirements to vet the list for our unit-vacancy promotions are onerous. We have tried to streamline the process inside the National Guard piece of this. We used to keep files for about 45 days and we have shrunk that down to two weeks. And the Army needs to do the same thing inside its process.

It’s not fixed yet. We continue to stay focused on it. We have begun to see some shortening of timelines trying to get it down to under 180 days, which would be about right. We just have to stay focused on the problem until we actually see that. I know the young officers out there that are waiting for their promotions to come through. I know it’s frustrating. Personally, I’m focused and engaged on it. From my standpoint, inside the National Guard process, there is not much more we can take out from 45 days down to two weeks. We’ve offered to put people into the Army staff to help them speed up the review of these things.

There seems to be a continuing level of friction between the Title 10 Guard in Washington, D.C., and the Title 32 Guard in the field. Perhaps it’s just a natural inside-the-Beltway versus outside-the-Beltway thing. Perhaps there’s more. After all, one is exclusively full time, the other predominately part time. And they serve different masters. What’s your take?

Bureaucracy is inherently in the way of people trying to get things done, and I realize that contributes to tensions between the field and Washington. That’s why we here in Washington are made up of people from the field. We exist for one reason at the National Guard Bureau, and that is to support and enable the 450,000 men and women who are in the states. Here, at NGB, we exist only to do that.

So we continue to have that mentality; that we need people on this staff to be from the states. They come here and bring current problems and current information on what’s impacting that soldier and airman in the field. That way, when we make decisions of policy, we can do it in a positive way that provides the ability to make the force the most lethal, best equipped it can be. I’m aware of the tension. I think sometimes it’s overblown. We are them.

You also mentioned at the National Capital Summit in July at NGAUS headquarters that Secretary Mattis’ voracious appetite for reading has more people at the Pentagon cracking books. How important is professional reading to an officer’s development, and what books are on your near-term reading list?

Secretary Mattis is renowned for his knowledge and the breadth and depth of his library. He says there are no new problems. They have all been worked before and they have all been solved before. It’s true. I don’t go to too many meetings where he hasn’t referenced a book. Generally, when he references a book, I go and read it.

I do read a lot, more than I used to. Right now, I’m reading a book called Bully of Asia: Why China’s Dream is the New Threat to World Order by Steven Mosher. It’s a very interesting read. I usually have two or three books going at the same time. I’m also reading The Last Lion, William Manchester’s three-book series on Winston Churchill. He lived in a fascinating time.

Reading is just hugely important. The more you can read about history, particularly military history and strategies, the better the leader you will be, especially the more senior you are. It’s impossible to read too much.

You came up through the ranks. What’s the best piece of enduring leadership advice you ever received?

I was once told that the most important job is the one you’re doing. I believe that. As you’re working as a junior officer or NCO, your job is to become tactically proficient in what you do and with those you lead. Always pay attention. You should always look out and take notes as you watch senior leaders, decide if something they say or do is something you would say or do if you progress to that level. There is value in both of those lessons. It’s what I’ve done, taking the best attributes of the best leaders I’ve been around. I like to think that is what I do now as a senior leader in the National Guard.