Texas Rangers

The Texas Rangers is the name of a state bureau of investigation so renowned for the grit and skill of its members that it inspired a television series and the name of a major-league baseball team.

But before it was a crime-fighting agency, the Texas Rangers was an early Lone Star State military organization.

The militia began in Texas about the same time as American settlers arrived. The original motivation for an organized force to protect them was recognized almost as soon as settlements started in 1821. Stephen F. Austin, the so-called Father of Texas, had inherited a land grant from his father, Moses Austin. The younger Austin was the first successful empresario, a term then meaning someone in charge of finding families to settle an area.

On Feb. 18, 1823, the emperor of the newly independent Mexico authorized him “to organize the colonists into a body of the national militia, to preserve tranquility.” Soon after, Austin’s militia unit was authorized to “make war on Indian tribes, who were hostile and molested the settlement.”

Austin’s militia soon battled raiding parties of Karankawa Indians, finally forcing them to stop. According to a study of the Texas militia, “Austin’s militia remained small and imperfect, relying on mostly small units recruited for the duration of an emergency.”

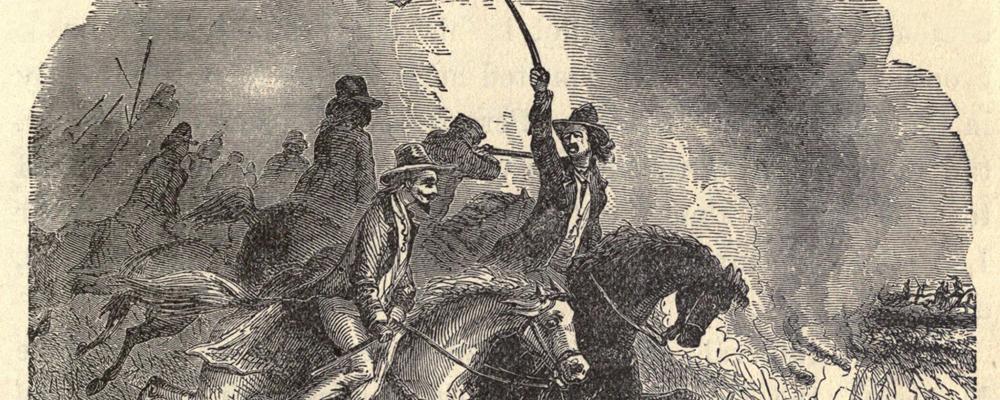

This was the period a far better-known competitor to the Texas militia emerged. Volunteer “ranging” cavalry companies had been established as separate organizations from regular militia, though they were considered a branch of the militia. These companies quickly became known as Texas Rangers, though the name did not become formal until after the Civil War.

Austin formed the first temporary ranger company in 1823 to protect his colony from local Indians. Further companies were raised, for limited terms of service, during the 1835-1836 Texas revolution from Mexico. Rangers fought in the Mexican War and handled Texas frontier defense during the Civil War.

However, the early rangers were best known for their role in fighting the local Indian tribes.

Historians sometimes still refer to Indian attacks on the American settlers as depredations. The term “attack” is less loaded. The Indians had different motives for going after white settlers. Primarily was that they resented people encroaching on their hunting grounds. Spain had never really settled Texas, but the Indians foresaw a more extensive American settlement.

The settlers didn’t usually consider the Indian point of view. They saw that one of the local tribes, the Karankawas, seemed to be taking every opportunity to attack any settlers caught alone or in small groups.

The problem grew worse. Historian Charles M. Robinson III, author of the 2000 study The Men Who Wear the Star, wrote, “Although the scrapes between Indians and settlers did not have the character of the systemized Kiowa and Comanche raids, encounters were frequent enough to demonstrate the need for some sort of organized frontier defense force.”

And the rangers, as history tells it, were equal to task. One writer said a Texas ranger could “ride like a Mexican, trail like an Indian, shoot like a Tennessean, and fight like the devil.”

One writer said that a Texas ranger could 'ride like a Mexican, trail like an Indian, shoot like a Tennessean, and fight like the devil'.

IN MAY OF 1823, the Mexican governor authorized recruitment of a frontier protection company, to be stationed near the mouth of the Colorado River. This can be considered the first Texas Ranger unit. The original rangers were usually short of ammunition. By July, the American alcalde (mayor) and a companion set out for San Antonio, with a letter from the ranger unit’s commander, to try and obtain ammunition.

About halfway through the 100-mile ride, they encountered three Indians. The companion urged caution, but the alcalde approached the Indians with his hand out. One of the Indian warriors pulled him off his horse and killed him with a lance. The companion escaped.

A few days after the attack, Austin’s grant of land for sale to settlers was confirmed. He was given authority to raise a regiment of the Mexican National Militia he would command as a lieutenant colonel. The rangers were still short of ammunition; funding for supplies was a problem for the rangers for decades.

A few weeks after Austin was appointed to organize, and lead, the militia regiment, five American colonists took a boat down the Colorado River to buy corn. On the way back, at Skull Creek, they were attacked by a group of Karankawa Indians.

A man named J.C. Clark was the only survivor of the attack, and his thigh was broken by a bullet. He managed to enter Skull Creek and swim to a canebrake — a dense growth of cane, or grass, often on the banks of a river or other body of water. Clark hid, trying to stop the bleeding — he must at least have slowed it down — until the Indians got bored looking for him and left.

The same day, 15 miles to the north, another settler ran into what was probably the same group of Indians. He thought they were friendly and rode toward them. One opened fire and severely wounded the settler.

When the attack was reported to Capt. Robert Kuykendall, in charge of the rangers in the Colorado River area, he organized a dozen settlers to go after the Indians. Near the mouth of Skull Creek, after nightfall, Kuykendall and two of his men scouted ahead for the Indians. They heard a thumping sound ahead of them in the dark. One of the men said it was wild turkeys. Another, however, thought the sound was Indians pounding brier root into food. The sound of a baby crying solved the mystery.

The three scouts brought the rest of the men up, leaving two men to watch the horses. Several Indians were killed in the attack, and the rest retreated. There is no indication the rangers ever found out who was responsible for the two attacks. Clark, still hiding in the canebreak, heard the fighting and made his way to the ranger camp. He lived a long time after his narrow escape.

The nighttime and the earlier engagements were the first fights with Indians in Austin’s colony. Austin used his new administrative powers to declare he would use his own resources to pay for 10 additional men to act as rangers for the common defense. This is likely the first time “Rangers” was applied to a Texas force. Ironically, no records have been found that these men were enlisted.

INDIANS WERE NOT THE ONLY CHALLENGE for the Anglo settlers, and the Rangers, up until the start of the Texas revolution in 1835. “Conventional” criminals crossed into Texas from bordering areas, primarily Louisiana and Mexico proper.

On occasion, criminals from the United States fled to Texas — without even going through the motions of legal settlement. The settlers did not always trust Mexicans to punish criminals, even for the serious offence of horse theft — stealing someone’s potentially-life preserving transportation.

A primarily Anglo-Texan convention opened in San Felipe on Oct. 11, 1835. It soon declared itself a Permanent Council to set up a government in Texas and establish an army. Problems with many of the Indian tribes continued, and the Texans saw the continued need for frontier defense.

Three companies were formed. Each Ranger — this is about when historians started capitalizing Ranger — would supply his own horse, weapons, ammunition and equipment. He would be paid $1.25 per day, not much money even at that time. Rangers would also be compensated for the loss of personal equipment. But the Texas government, not just the Rangers, would be chronically short of money until the oil boom of the early 20th century.

February through April 1835 were occupied with fighting the Mexican army under Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Most incidents with Indians involved smaller tribes in closer proximity to the Anglo settlements. However, the Texans began to run into the larger and more powerful Comanche tribe.

The Comanches had ignored the Anglos at first. But soon other tribes were pushed into Comanche hunting areas. When the Anglos moved further west, they began to hunt and decrease the size of the same buffalo herds on which the Comanches depended, they began to fight back.

The second half of the 1830s saw a series of raids, despite treaties with the Comanches, but the fighting did not really step up until the Council House fight of 1840. On Jan. 9, 1840, three Comanches brought a Mexican prisoner to San Antonio. They said they had been sent to arrange peace negotiations with the Texas authorities.

The message was sent to the Texas Secretary of War, Albert Sydney Johnston — later a senior Confederate general. Johnston relayed that he would give the Comanche chiefs safe passage to and from San Antonio, if they brought all their Anglo captives with them as a sign of good faith. Otherwise, the chiefs would be held as hostages.

The Comanches returned Jan. 19 with only one white female captive. She showed signs of serious abuse and torture. Twelve senior chiefs, part of the group of Comanches who came to San Antonio, were escorted into a building known as the Council House. The other 50 or so Indians remained in the courtyard. The white captive told the Texas soldiers that other captives were being held at the main Comanche camp. They would be brought in one or two at a time in the hopes of large and continuous ransom payments.

Troops were brought in the room, and the chiefs prepared their knives and bows. They were told to open fire if the Indians did not surrender calmly. One chief stabbed a sentry and was shot. The others attacked the soldiers but were quickly killed. When they heard the shooting inside, fighting broke out in the courtyard. When the shooting stopped, 30 chiefs and warriors, including those killed inside, and five women and children were dead, 29 were prisoners. Seven soldiers and bystanders were killed, eight wounded.

AN UNEASY TRUCE prevailed for the next few months, as the Comanches recovered from the loss of so many chiefs. There were negotiations with Texans over prisoner exchanges.

The Comanches were planning a revenge raid, which started in August 1840. On Aug. 4, a war party of about 600 Comanches and allied Kiowas left the hill country and moved onto a sparsely inhabited part of the plains nearer the coast.

After raiding several towns, the Indians headed back to relative safety in the hills to the west. Rangers at Plum Creek intercepted them, for one of the larger battles in the Indian-Texan wars. The last major battle for the Comanches, against the U.S. Army, did not occur until 1874.

The rest of the prewar history of the Texas Rangers consisted primarily of chasing and fighting Indians and bandits. It included much of the 1850s trying to stop a well-organized group led by Juan Cortina. The Indian “problem” increased during the Civil War with the absence of the federal and Confederate armies and many experienced Rangers serving with the Southern armies.

The Texas militia was abolished in 1866 by the federal reconstruction government, and not replaced until 1870. The Rangers had been replaced by the State Police for three years during Reconstruction. On April 10, 1874, the Frontier Battalion of Texas Rangers was created. This is the direct ancestor of the current Texas Rangers. The first militia units formed, including the Houston Guard, are direct ancestors of the current Texas National Guard.

The Texas Rangers did not cease to exist when post-Reconstruction Texas fully reestablished a militia system. In 1935, they formally became the Texas Ranger Division of the Department of Public Safety. This was two years after the most famous Texas Ranger, though fictitious, the Lone Ranger, premiered as the main character of a radio, and later television, drama.

The Rangers still range, as they are a statewide police organization with authority throughout all of Texas. They handle normal police functions when requested to support local law enforcement forces — or when judicial or political authorities rule that a local police force cannot handle a situation. They investigate and work to suppress organized crime.

Bruce L. Brager is a New York-based freelance writer who specializes in military history. He can be reached via magazine@ngaus.org.